Acupuncture is a frequent topic on this blog because it’s the perfect example of the failure of evidence-based medicine (EBM). The modality, which involves sticking thin needles into the skin along various “meridians” so that they “unblock the flow of qi” (qi being the “life energy” or “vital force”) in order to treat…well…just about everything is a classic example of a prescientific treatment that ignores anatomy, given that the “acupuncture meridians” into which the needles are stuck do not correspond to any known structure. If you believe its advocates, acupuncture is useful to treat such a wide variety of illnesses and symptoms that it beggars imagination. Pain, infertility, menopausal hot flashes, constipation, migraines, Parkinson’s disease, chemotherapy-induced nausea, post-traumatic stress disorder, fibromyalgia, carpal tunnel syndrome, asthma, anxiety, depression, acute bronchitis, diarrhea, allergies, low libido, and a lot more. And those are just the conditions that the World Health Organization mentioned, not the ones that acupuncturists claim, which is a more expansive list. Of course, acupuncture can also help you lose weight, if you believe advocates, because why not? If there’s a rule of thumb about medicine that works pretty well, it’s that if a treatment is recommended for everything chances are good that in reality it treats nothing. Indeed, as our fearless leader Steve Novella and his collaborator once stated, acupuncture is a “theatrical placebo.”

We’ve discussed so many studies of acupuncture on this blog that it’s hard to remember, find, or list them all. However, in general, we’ve pointed out how, the claims of its advocates notwithstanding, the advocates’ own studies show that acupuncture doesn’t work for menopausal hot flashes (or hot flashes due to the antiestrogen treatment used for breast cancer), pain, infertility, asthma, lymphedema (also here), depression, and just about anything else. (And acupuncture especially doesn’t work in the emergency room or on the battlefield or in the Veterans Administration). Unfortunately, it appears to be time to dive in again, because another acupuncture study is making the rounds. It was published in JAMA in July, and somehow I missed it. However, my attention was drawn back to it a few days ago, when I was catching up on my journal reading and came across a Medical News & Perspectives article by Jennifer Abbasi entitled “Can Acupuncture Keep Women on Their Breast Cancer Drugs?” in the August 28 issue. Fortunately, this gave me the opportunity to discuss the trial.

Let’s dig in, shall we?

The problem of hormonal therapy for breast cancer

Hormonal therapy for breast cancer is indicated for hormone-responsive breast cancer. What “hormone”-responsive generally means is that the cells in the tumor express the estrogen and/or progesterone receptor on their surface. Blocking the action of estrogen in these tumors can thus be an effective treatment, either adjuvantly to prevent recurrence after successful surgical treatment of breast cancer or as a primary first treatment for metastatic disease. Indeed, the responsiveness of some tumors to estrogen was first suspected in the late 1800s, when Thomas William Nunn reported the case history of a perimenopausal woman with breast cancer whose disease regressed 6 months after her menstruation ceased. At the time estrogen had not yet been isolated (that wouldn’t happen until 1929), but this observation strongly suggested a link between ovarian function and breast cancer, as did another report of a woman with breast cancer who experienced a spontaneous remission after menopause by A. Pearce Gould in 1896.

This link was also established in 1895 when George Thomas Beatson removed the ovaries of a woman with metastatic breast cancer with extensive soft tissue involvement and achieved a complete remission that lasted for four years. Beatson also treated the woman with thyroid extract, which was being used at the time to treat various ailments based on George Redmayne Murray’s report of successfully treating a patient who had myxedema with sheep thyroid extract. That it was the oophorectomy and not the thyroid extract was demonstrated by Stanley Boyd, who performed oophorectomy on five women with inoperable breast cancer, one of whom survived 12 years, publishing data in 1900 indicating that one-third of patients undergoing oophorectomy clearly benefited. (Given that roughly two-thirds of breast cancers are estrogen-responsive, we now know that that was about half of the patients with estrogen-responsive cancers deriving a clinical benefit.) He therefore championed oophorectomy as a useful, albeit not curative, treatment for breast cancer. Unfortunately, oophorectomy, as was the case for any pelvic or intraabdominal surgery in the early 1900s, had a high rate of mortality and complications; so this treatment never caught on until the 1950s, when Charles Huggins and Thomas Dao brought oophorectomy combined with adrenalectomy back to the mainstream of breast cancer therapies.

Then came the advent of Tamoxifen. This particular drug’s history is quite interesting. Tamoxifen was first made in 1966 by scientists working for Imperial Chemical Industries Pharmaceuticals (ICI, now AstraZeneca). These scientists had been tasked with finding a new emergency contraceptive. Unfortunately, early versions of the drug had no contraceptive effect in humans, and the drug was almost abandoned. However, V. Craig Jordan re-invented this failed “morning-after pill” to treat estrogen receptor-positive [ER(+)] breast cancer. A clinical trial demonstrated its effectiveness and the drug was licensed in the UK in 1972.

Of course, these days, we have a lot more than Tamoxifen to treat ER(+) breast cancer. There’s another class of drug known as aromatase inhibitors, as well as others. Basically, they fall into two categories; drugs that block estrogen’s action (e.g., Tamoxifen and Faslodex®) or drugs that block the production of estrogen (aromatase inhibitors). In some patients, ovarian function is blocked using “chemical castration” with drugs such as Zoladex® and Lupron®.

Given that over two-thirds of breast cancers are estrogen-responsive, there are a lot of patients undergoing treatment with estrogen-blocking drugs. Unfortunately, these drugs can often have a serious deleterious effect on a woman’s quality of life, causing menopausal symptoms in premenopausal women and worsening menopausal symptoms in post-menopausal women. These symptoms, particularly hot flashes, are very hard to treat with anything other than estrogen. Indeed, I still remember the first patient I ever operated on as a new attending and how she simply could not tolerate her Tamoxifen, no matter how much her oncologist tried to work with her to make it possible for her to take it. The seriousness of the effects of these drugs on patient quality of life should not be underestimated.

One significant potential complication associated with aromatase inhibitors (almost always the first choice of antiestrogen drug for postmenopausal women) is osteoporosis. However, the most vexing side effect for most women on these drugs is severe musculoskeletal pain, specifically arthralgia (joint pain). The mechanism causing this joint pain is poorly understood, but it can be debilitating enough that the only choice is to stop the medication. This brings us to the rationale for the study, as described by Ms. Abbasi:

A class of drugs called aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are a cornerstone of breast cancer treatment, but they come at a steep physical price. About half of women who take this form of hormone therapy develop arthritis-like joint stiffness and pain for still-unknown reasons.

“When we started using these medicines, the first thing that women would say is, ‘This medication makes me feel like an old lady,’” said oncologist Dawn Hershman, MD, who leads the breast cancer program at Columbia University Medical Center’s cancer center in New York City.

The drugs—anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole—are prescribed for 5 to 10 years in postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive breast cancer, but the life-limiting pain they cause compels many to abandon the treatments before that. And it’s feared that this could lead to cancer recurrence and death.

You can tell where this is going next:

Eight years ago, in an effort to encourage women to keep taking their AIs, Hershman and her collaborators set out to find a way to alleviate the pain. A pill wouldn’t cut it. “We know that when a patient has side effects from the medicine, they don’t want to take another medicine that has the potential to cause more side effects,” she said. “Natural remedies or modalities are more acceptable to patients.”

So they chose to study acupuncture, a form of traditional Chinese medicine that some clinical evidence suggests can effectively treat chronic musculoskeletal pain. The results from their National Institutes of Health–funded randomized clinical trial recently appeared in JAMA.

Yes, we had a medical problem whose solution we haven’t determined yet; so let’s try magic. Why not? Of course, the evidence cited that acupuncture could treat chronic pain was nothing more than an update of a meta-analysis that was extensively discussed here when the first version came out and has nothing new that changes my conclusion about it. In any event, the study reported on by Abbasi is, as you will see, not very convincing.

Blinded by the light (reflected off the shiny needle)

Let’s take a look at the study, “Effect of Acupuncture vs Sham Acupuncture or Waitlist Control on Joint Pain Related to Aromatase Inhibitors Among Women With Early-Stage Breast Cancer“, by Dawn L. Hershman, MD, MS; Joseph M. Unger, PhD, MS; Heather Greenlee, ND, PhD; et al. Dr. Hershman, as was noted above, is based at Columbia University. Heather Greenlee, ND, you might recall, is a naturopath (i.e., the ND stands for “Not-Doctor”) based at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. We’ve met her before, most recently when the guidelines for the “integrative oncology” care of breast cancer patients published by the Society for Integrative Oncology (SIO) were endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The study involved eleven academic medical centers and clinical sites, which recruited: Women with early stage ER(+) breast cancer who scored at least 3 on the Brief Pain Inventory Worst Pain (BPI-WP) item (score range, 0-10; higher scores indicate greater pain) and who were either (1) postmenopausal and taking an aromatase inhibitor or (2) pre- or perimenopausal whose ovarian function had been suppressed with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and were taking an aromatase inhibitor. Exclusion criteria included prior acupuncture treatment for joint symptoms at any time; history of bone fracture or surgery of the affected joints within 6 months prior to enrollment; severe bleeding disorder; or a latex allergy. Also, study participants must not have received opioid analgesics, topical analgesics, oral corticosteroids, intramuscular corticosteroids, or intra-articular steroids, or any other medical therapy, alternative therapy, or physical therapy for the treatment of joint pain or joint stiffness within 28 days prior to registration. The trial ran from March 2012 to February 2017 (final date of follow-up, September 5, 2017).

Patients were randomized in a 2:1:1 ratio to receive either true acupuncture, sham acupuncture, or to be on a wait list. As for the acupuncture used:

The acupuncture study interventions were developed by a consensus of acupuncture experts based on previous studies of acupuncture for aromatase inhibitor–related arthralgias with adherence to the Standards for Reporting of Controlled Trials in Acupuncture (STRICTA) recommendations.13 The details of the acupuncture point protocol (ie, body site of needle placement) and extensive training and standardization methods (in-person training, study manuals, monthly phone calls, and remote quality assurance monitoring) have been previously described.17

Briefly, both true acupuncture and sham acupuncture consisted of twelve 30- to 45- minute sessions administered over a period of 6 weeks (2 per week) followed by 1 session per week for 6 weeks. For true acupuncture, stainless steel, single-use, sterile and disposable needles were used and inserted at traditional depths and angles. The joint-specific protocol was tailored to as many as 3 of the patient’s most painful joint areas.18 Needles were restimulated manually once during each session. The sham acupuncture consisted of a core standardized prescription of minimally invasive, shallow needle insertion using thin and short needles at nonacupuncture points. The sham acupuncture protocol also included joint-specific treatments and an auricular sham based on the application of adhesives to nonacupuncture points on the ear. The waitlist control group received no acupuncture treatments and received no other intervention for 24 weeks after randomization. At 24 weeks, all patients received vouchers for 10 true acupuncture bonus sessions to be used prior to the 52-week visit.

The reason I quoted that so extensively is so that you can see any issues I point out (and because the article is behind a paywall). This is not an unusual sham control procedure, using needles in nonacupuncture points. I must admit, I had a heck of a time finding the one thing I immediately look for whenever I see a trial design like this, the answer to the one question I always have about any acupuncture trial: Was it double-blinded? Yes, the authors state that it was impossible to blind the wait list control, but that’s OK. That’s what wait list controls are for: To estimate the magnitude of placebo effects. Not blinding the wait list control is fine. Then it dawned on me! Of course this trial wasn’t double-blinded. The acupuncturists knew they were sticking needles in non-acupuncture points. Indeed, in Abbasi’s article, the authors try to justify not using a double blind design and having only the patients blinded to group:

Still, Hershman knows critics will take issue with the sham treatments, which weren’t double-blinded. Practitioners knew they were giving fake treatments and may have sent subconscious signals to their patients.

Using retractable needles designed to blind practitioners to the sham wouldn’t have helped, Hershman said, because studies suggest that both patients and acupuncturists can tell the difference.

“We looked at a whole slew of studies…of different sham modalities,” Hershman said. “They all had advantages and disadvantages. We felt in looking at the collective literature out there that this was probably the best approach.”

Yes, I do take issue with the sham treatments. It’s simply not true that sham needles don’t work. I’ve lost track of the number of studies I’ve read where sham retractable needles were used and double-blinding was fine. My guess is that the acupuncturists probably didn’t want to use them. So right away, you know all the crowing about how “rigorously designed” this trial was in Abbasi’s article is a load of fetid dingos’ kidneys, especially given that subjects in the true acupuncture group were more likely to believe that they were receiving true acupuncture (68%) than those in the sham group (36%). Yeah, the masking worked real well there! I’ll grant that the rest of the study was pretty well-designed, particularly given that a waitlist control was included, but the inadequate blinding, along with other factors, should be enough to invalidate the results of the study, as I’ll explain.

Before I go into the results, though, let’s look at the endpoints to be assessed. The first prespecified primary endpoint used the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF), which consists of 14 questions asking the subjects to rate their joint pain over the prior week and the degree to which the pain interferes with activities using a 0- to 10-point scale. Thus, the primary end point was the BPI Worst Pain Item (BPI-WP) score at 6 weeks of treatment, with the authors noting that a reduction of 2 points on the BPI-WP has been identified as a clinically meaningful change for a patient.

Secondary endpoints included a number of measurements, including:

- Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) worst pain, worst stiffness (items 15 & 16), pain severity, and pain-related interference scores at 6, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 52 weeks.

- Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (pain, stiffness, and function) for the hips and knees at 6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks.

- Modified-Score for the Assessment and Quantification of Chronic Rheumatoid Affections of the Hands (M-SACRAH) (pain, stiffness, and function) at 6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks.

- PROMIS Pain Impact-Short Form (PROMIS PI-SF) at 6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks.

- Quality of life as assessed by the FACT-ES Trial Outcome Index (Version 4) at 6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks.

- Functional testing of the hands (grip strength) and legs (‘Timed Get Up and Go’) at 6, 12, 24, and 52 weeks.

- Analgesic and opioid use at 2, 4, 6, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 52 weeks.

- Aromatase inhibitor (AI) adherence at 12, 24, and 52 weeks.

- Urine AI metabolites at 24 and 52 weeks.

- Serum hormone biomarkers (estradiol, FSH, LH) and inflammatory biomarkers (serum TNFα, IL-6, IL-12, CRP; urine CTX-II) at 6, 12, and 24 weeks.

There were others, but these are the most relevant. As for the analysis:

For a 2-point difference between groups and an assumed 3.0-point standard deviation at 6 weeks, 208 eligible patients were required for 82% power (using 2-sided tests; α = .025) for true acupuncture vs sham acupuncture and true acupuncture vs waitlist control. The design further specified an estimated 5% nonadherence and 10% dropout rate at the primary end point evaluation time of 6 weeks. In addition, the design incorporated a 10% contamination rate. The primary outcome was analyzed using the intention-to-treat principle (ie, as randomized), using a complete-case approach given limited missing data (<10%), without using imputation.

So let’s see what the results were. Those of you who’ve read ahead or read more of the actual study and/or Ms. Abbasi’s article know that the authors reported a “positive” result that was quite underwhelming. Surprise, surprise! I know.

The theatrical placebo that is acupuncture remains theatrical

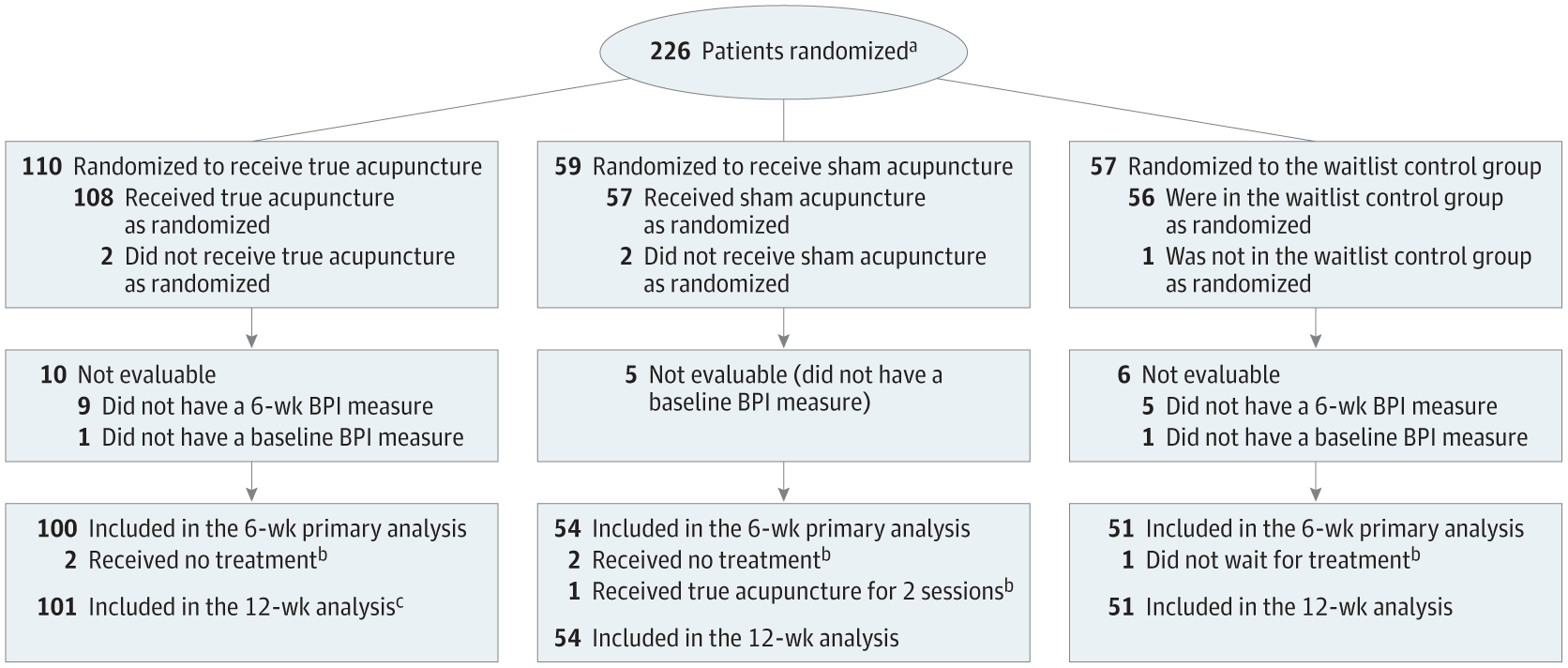

Overall, 226 patients were randomly assigned to the true acupuncture (n = 110), sham acupuncture (n = 59), or waitlist control (n = 57) group according to the diagram below:

Interesting observations include:

- The median age was lower in the sham acupuncture group (57.0 years) than in the waitlist control (60.6 years) or true acupuncture (60.8 years) groups.

- Fewer Hispanic patients were randomized to the waitlist control group.

- More Asian patients were randomized to the true acupuncture group (10% compared to 3% in the sham acupuncture and 4% in the wait list control).

Overall, the groups were pretty similar in relevant characteristics, although one has to wonder if having more Asians in the true acupuncture group could have affected the results, given the cultural affinity for traditional Chinese medicine, but who knows? I couldn’t find any investigation whether that was the case.

So let’s look at the primary outcome:

Compared with baseline, the mean observed BPI-WP score was 2.05 points lower (reduced pain) at 6 weeks in the true acupuncture group, 1.07 points lower in the sham acupuncture group, and 0.99 points lower for the waitlist control group, with differences in adjusted 6-week mean BPI-WP scores between true acupuncture vs sham acupuncture of 0.92 points (95% CI, 0.20-1.65; P = .01) and between true acupuncture vs waitlist control of 0.96 points (95% CI, 0.24-1.67; P = .01).

Remember how the authors stated that they had hoped to see a change in the pain score of greater than two? They didn’t get it. As is often the case in clinical trials, everyone got better, including the waitlist control group, and in the end there was a statistically significant difference in the change in pain score, but that difference is by definition almost certainly not clinically significant. Yes, it’s exactly the same thing the Vickers meta-analysis found back in 2012: A statistically significant difference, but a difference too small to be clinically relevant.

What about all the secondary endpoints? Well, if you really look at the data, the only consistent finding is that the true acupuncture group had lower pain scores than the waitlist control by all measures used. Given that no correction for multiple comparisons was made for secondary analyses, I have no idea what to make of these results; certainly I was unimpressed by the findings of differences between true and sham acupuncture for some measures but not others.

As for the primary outcome measure, in the mixed effects model:

Through 24 weeks, adjusted mean BPI-WP scores were 0.59 points lower (95% CI, 0.34-1.14; P = .04) in the true acupuncture group compared with the sham acupuncture group and were 1.23 points lower (95% CI, 0.66-1.80; P< .001) in the true acupuncture group compared with the waitlist control group

So there was a (barely) statistically significant effect of true over sham acupuncture remaining at 24 weeks, but the only real difference was, as expected, between true acupuncture and waitlist. This brings me back to the issue of blinding, where, as I mentioned above, patients in the true acupuncture group were considerably more likely than those who received sham acupuncture (68% versus 36%; p < 0.001) to believe that they had received “true acupuncture.” The authors try to wave this away by stating that the intervention effect for BPI-WP did not differ between those believing vs not believing they were receiving true acupuncture when interaction tests were applied, noting that P for interaction = 0.16. Remember how I said that statistically significant ≠ clinically significant? Well, it’s also true that statistically insignificant does not necessarily mean an effect is insignificant. Remember, the cutoff for statistical significance is p<0.05, but that’s an arbitrary cutoff. Basically, a p-value less than 0.05 implies that there’s only a 5% chance of observing the difference found (or a larger difference) if the null hypothesis (i.e., that there is no difference in the value measured between the two groups) is true. Yes, P=0.16 is not considered anywhere near statistically significant and I won’t try to argue that it is, but it’s low enough that I wouldn’t be nearly as confident as the authors are that there was that there was no interaction at all between the masking and the intervention effect. Think of it this way: P=0.16 implies 16% chance of getting the observed result (or more extreme result) if the null hypothesis is true. That’s still rather low, just not what anyone would accept statistically. If the p-value were something like 0.5 I’d be absolutely down with the conclusion that there was no interaction between a subject’s perception of which group she was in and whether an effect was observed. Right now, I’m not so sure.

I’m sure I’ll be ripped by a statistician somewhere who was pulling his or her hair out while reading the above paragraph because I’m being too simplistic, but such is the risk I take as a scientist who’s had a biostatistics course or two and not an actual statistician. (This is as close to humility as you’ll likely see me.) So I might as well go all in and phrase it in a way that might annoy even more people. Think of the p-value as an estimate of how likely it is that the difference you found between the groups you’re comparing is not real, and then 0.16 (or 16%) doesn’t sound quite so reassuring, although it’s perfectly fine as being “statistically insignificant”. Think of it yet another way. You have a 16.666667% chance of rolling a one on a six-sided die. How many times have you observed that? Quite a few, I’ll bet.

Hopefully, though, one thing we can all agree on is that post hoc analyses are often abused, because the authors, having found not much of anything particularly convincing (a clinically nonsignificant difference in pain scores between the true and sham acupuncture groups that’s not particularly strongly statistically significant), clearly weren’t happy. So they compared the percentage of patients in each group who achieved as their primary measure a 2-point or greater BPI-WP at 6 weeks. What they found was that the number of those experiencing that level of decrease in BPI-WP was was 58.0% (n = 58) for the true acupuncture group, 33.3% (n = 18) for the sham acupuncture group (RD, 24.7% [95% CI, 8.8%-40.5%]; RR (relative risk), 1.64 [95% confidence interval, 1.10-2.44]; P = .02), and 31.4% (n = 16) for the waitlist control group (difference for true acupuncture vs waitlist control, 26.6% [95% CI, [10.6%-42.6%]; RR, 1.75 [95% CI, 1.13-2.69]; P = .01; eFigure 2 and eTable 2 in Supplement 2). The authors at least admit that the post hoc analysis was hypothesis-generating, which is all that post hoc analyses are generally good for.

The spin

Ms. Abbasi’s story appears to me to be in essence an attempt to spin a study with very unimpressive results and, when you come right down to it, failed to reach its primary endpoint. That doesn’t stop JAMA from taking what I view to be an extraordinary step. It’s not the authors so much who are defending their study, but rather JAMA editors, Deborah Schrag, MD, the associate editor who handled the article, and Ed Livingston, MD, a deputy editor at JAMA. I can’t recall ever seeing this in an op-ed published in JAMA before:

“In the formal sense, this study did not reach its primary end point,” said Deborah Schrag, MD, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston and the JAMA associate editor who handled the article. But, she added, “they did achieve a clear and consistent reduction in women’s symptoms.”

No, they didn’t, for reasons I explained in my usual fashion above.

Next up:

Ed Livingston, MD, a deputy editor at JAMA, said there is some debate regarding how to interpret the findings of a study when the primary end point is negative but many of the secondary end points trend in the positive direction, suggesting an effect of the intervention. “Some believe this is good enough to conclude that an intervention is effective,” he said.

Those “some” who believe that are likely acupuncturists and “integrative oncologists” who believe in acupuncture. In fairness, he’s not entirely wrong. There are always physicians who are willing to prescribe treatments they believe in based on weak evidence like the evidence in this study. That doesn’t make it right.

Finally, before we get to Dr. Hershman again:

Acupuncture’s unknown mechanism of action is also likely to arouse criticism. Schrag understands the skepticism. “I agree that that’s perturbing about acupuncture,” she said, “but when there are rigorous studies that demonstrate a benefit, I think it’s still hard to ignore. If this were a very toxic or expensive intervention, there might be less enthusiasm, but acupuncture is widely available and well known to be quite safe.”

Except that this study didn’t really show a benefit, except maybe if you squint your eyes real hard and wish as hard as you can. I can’t help but think that Dr. Schrag is feeling some heat over the decision to publish this study in a journal as prestigious as JAMA.

Finally, take it away, Dr. Hershman:

But at the end of the day, Hershman’s belief is that it doesn’t really matter why acupuncture works, as long as it does: “Ultimately what matters is making sure that patients feel better and stay on their medicine. If 60% of patients had a significant reduction [in pain], then I think that we may have done them a real service.”

The problem, of course, is that, when you take into account the lack of blinding of the acupuncturists and other shortcomings Dr. Hershman’s study is most compatible with acupuncture having no detectable effect above placebo on the joint pain caused by aromatase inhibitors. If I were to go all Bayesian on her, I’d point out that taking into account the prior probability of acupuncture working for this condition based on what we know would rapidly render the posterior probability that the observed result is correct to a very low value. This is just another crappy acupuncture study that doesn’t show what its authors think it shows and is already being used to promote quackery in oncology in the name of “integrative oncology”.